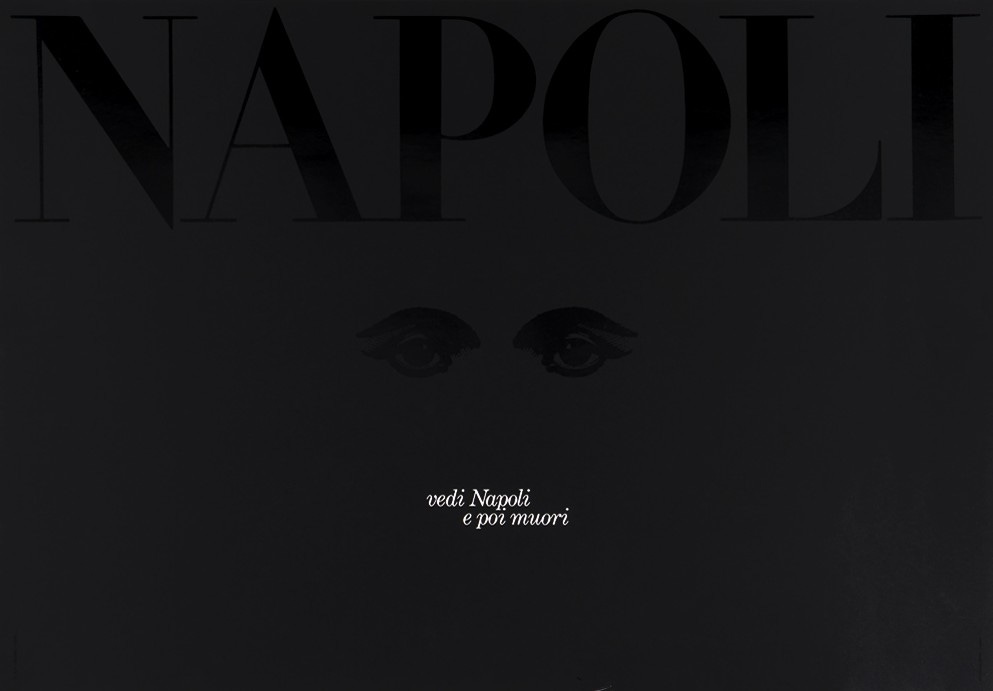

Whether it is graphic design or a piece of writing, what makes it emotionally powerful is often what is left out rather than what is included. Or as the legendary designer Massimo Vignelli argued, “it’s the space you put between the notes that make the music.”

Actually, Vignelli isn’t the only one to take notice of how music is made in such a way. From C…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Creative Discourse to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.