We are all imposters

Adulthood is basically just waking up and doing one’s best impersonation of a “grown-up.”

I am convinced we are all imposters. Or, at the very least, we all feel like it from time to time.

Actually, I think that feeling of “imposter syndrome” is a pretty natural response to achieving almost anything in life. For most people, there’s a natural and lingering sense of doubt about their own ability that inherently raises a few feelings of inadequacy from time to time — even when their accomplishments demonstrate otherwise.

Whenever I have my writing published somewhere, for example, I feel as if I’ve successfully cozened yet another editor into foolishly thinking my work is better than it actually is.

And I’m not alone.

As it turns out, most creative individuals tend to suffer from a similar disbelief in the worth of their own work — including individuals who are far more brilliant than myself and have infinitely more impressive accomplishments to their name than my paltry list of published works.

Albert Einstein, for example, once said of his own success that “the exaggerated esteem in which my lifework is held makes me very ill at ease. I feel compelled to think of myself as an involuntary swindler.”

Maya Angelou once confessed whenever her work was sent to print, she would think “uh oh, they’re going to find out now. I’ve run a game on everybody, and they’re going to find me out.”

Pulitzer Prize winning author John Steinbeck was convinced he had unwittingly played a con on the entire literary world, saying “I am not a writer. I’ve been fooling myself and other people.”

Even Vincent Van Gogh, arguably one of the most celebrated painters of all time, lamented that he felt “terribly inadequate,” saying “it is always my great fear that my art will appear so awkward and unfinished that people will take me for a madman.”

Now, to be fair, Van Gogh was a madman. And considering how little love his artwork received in its day, his feelings of inadequacy are as understandable as they are tragic. Nonetheless, the point still stands that even the world’s most talented human beings have often felt as if they’re simply “faking it” through their chosen field.

And they’re kinda justified in thinking so. To a great degree, we’re all just “faking it” through life — and not only in our professional capacity.

As a child, for example, most of us probably imagined we would eventually become grown-ups who have all the answers. The truth, as it turns out, is that most of us are instead just as confused as ever — but now we have bills and “responsibilities” to deal with on top of all the confusion, chaos and uncertainty of life.

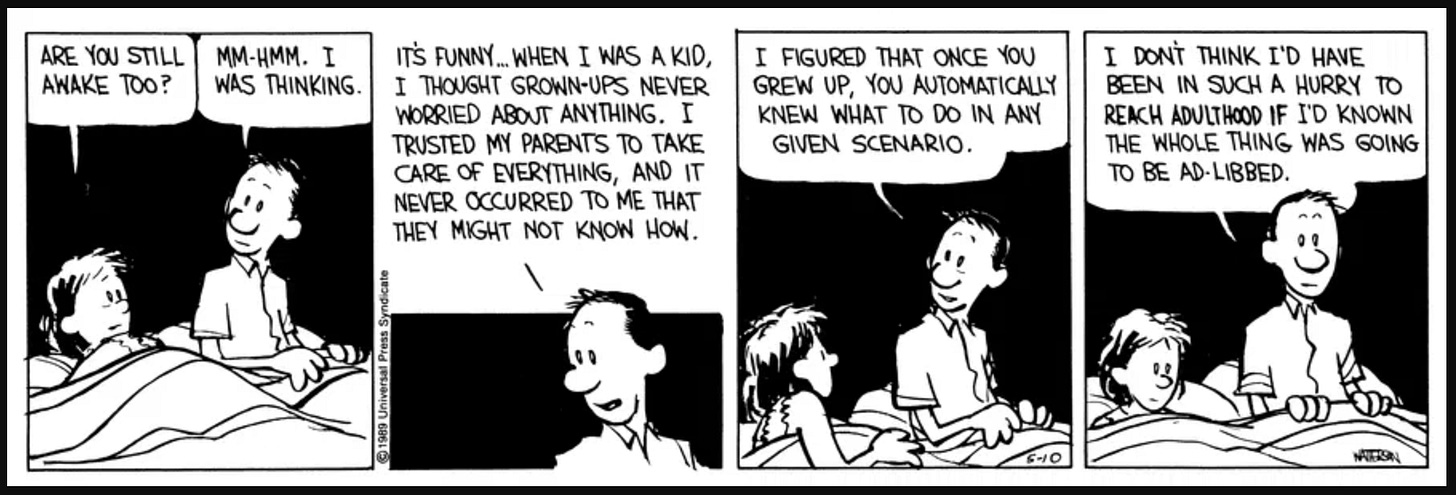

The older we get, the more apparent it seems that adulthood is actually little more than waking up in the morning and spending the day doing our best impersonation of a grown-up. Or, to paraphrase Calvin’s dad from the comic strip Calvin and Hobbes, “adulthood” is pretty much just adlibbing our way through life:

The reason life so often feels this way is because no matter how much wisdom we might accumulate over the years, we’re always encountering new things for which we have not grown completely prepared.

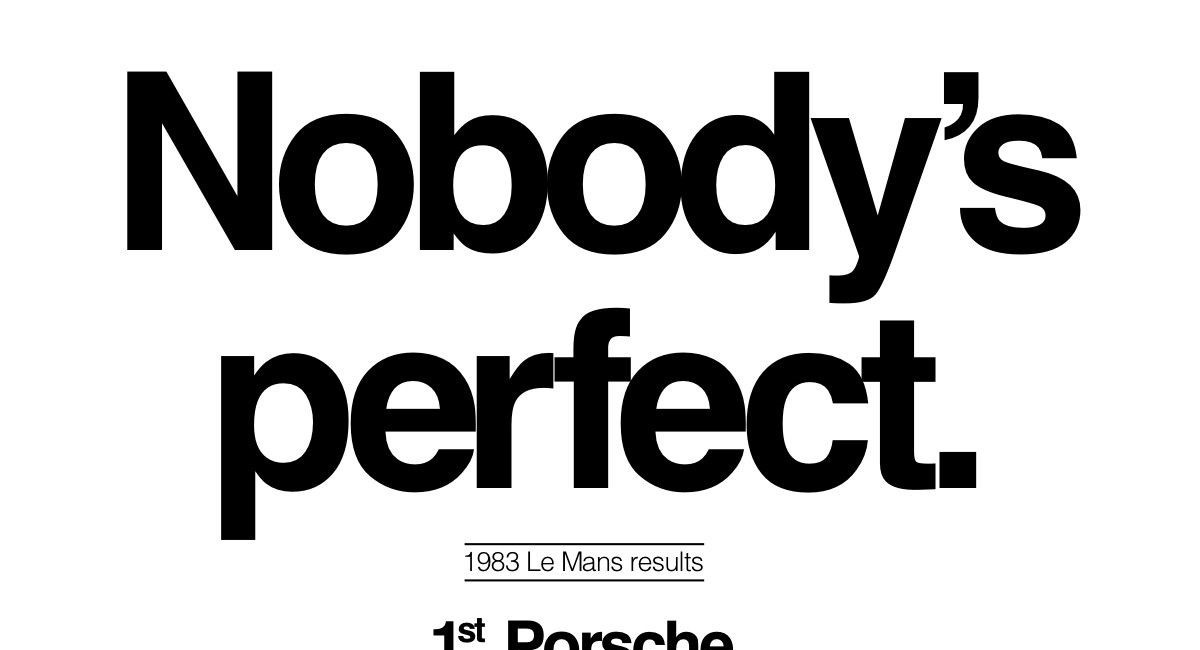

And in a professional context — especially in fields that demand a high degree of creativity — this is perhaps more poignant than elsewhere in our lives. If you’re innovating, creating something new or establishing your own path, you are (by definition) doing something beyond your lived experiences and therefore have no roadmap or Ikea-style set of instructions helping you along.

In other words: You’re making it up as you go. (In that light, it would actually be surprising if people who manage to succeed in their creative endeavors didn’t occasionally feel as if they were fooling everyone.)

And that reminds me of something else Van Gogh jotted down in his diary that always stuck with me: “I am always doing what I can't do yet, in order to learn how to do it, and this is how I think I'm going to be a great artist someday.”

In most of our pursuits, we learn on the fly. Whether it’s writing, starting a new business or merely navigating life’s multitude of personal challenges, we learn how to do what is necessary by actually doing it. We strike out, pretend we’re not terrified of failure, and begin tackling things with a perverse (and often superficial) confidence that maybe we will learn enough along the way to make things work.

When such foolish bullheadedness offers a taste of accomplishment or success, it’s often hard to accept it’s all due to raw skill or extensive expertise. After all, whatever “expertise” we’ve gained wasn’t there when we began the journey — and looking back it’s easier to recognize just how little we really “knew” when we began.

The more we experience that retrospective realization that we’re blundering through life, the more it occurs to us we probably don’t really know much about where we’re headed either. We never really “master” how to love, how to persuade those around us or how to deal with what life has to offer us — we merely get marginally better at it as we pretend our way from one day to the next.

In other words, anyone who is trying to build their own life will, at times, feel that sense of imposter syndrome.

The reason brilliant minds such as Einstein, Steinbeck and Angelou were so pestered by the nagging sense that they were fooling everyone is because (like all of us) their talent was not something born within them fully formed — it was something they developed through years of improvising their life choices and pushing themselves “to do what they couldn’t yet do,” until they could.

Maybe, if the rest of us keep at it long enough, we too can become “a great artist someday”… or at the very least, good enough to fool people into thinking we are.

Michael Schaus is a communications and branding expert based in Las Vegas, Nevada, and founder of Schaus Creative LLC — an agency dedicated to helping organizations, businesses and activists tell their story and motivate change.

From the Archives:

There’s no ‘paint by numbers’ kit for creativity

There are two main types of people who “color outside the lines” on a regular basis: Those who don’t wish to be constrained by some predetermined path, and those who simply lack fine motor skills.